Tripura Academician Argues Kok Borok’s Resurgence Fueled by Digital Storytelling, Not Just Formal Recognition

Professor Sunil Kalai, a Tripura-based filmmaker, photographer, and social activist, has asserted that language, specifically Kok Borok, transcends mere communication, embodying the very essence of history, culture, and identity. This statement comes amidst his research highlighting the pivotal role of digital media in preserving and promoting the indigenous language.

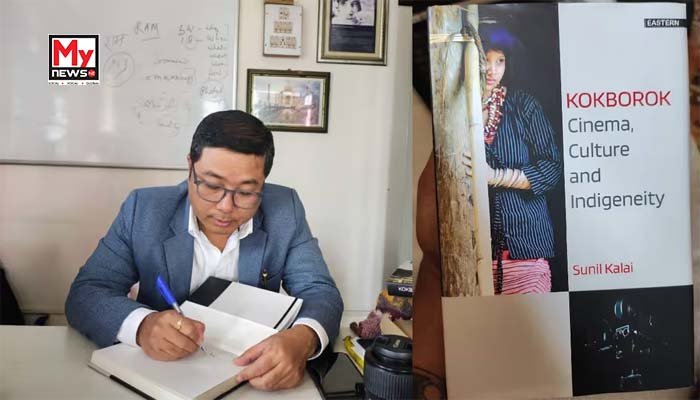

Kok Borok, spoken by the indigenous people of Tripura and parts of Bangladesh, has for decades been a subject of cultural and political debate. Professor Kalai, an Assistant Professor at Tripura Central University, has delved into the language’s evolution and its representation in cinema and digital media in his book, “Kok Borok, Cinema, Culture and Indigeneity,” based on his doctoral research.

In an interview, Professor Kalai clarified that his book is more than a simple record of language and film; it is a profound exploration of Kok Borok’s historical and cultural foundation. He explained that his work traces the language’s historical journey, the geopolitical circumstances surrounding its speakers, and their efforts toward political empowerment. He noted that while political narratives often create divisions between indigenous tribes and the Bengali community, the reality is far more intricate, with the language itself symbolizing resilience and a persistent struggle for recognition.

Professor Kalai emphasized that the discourse surrounding Kok Borok has been historically influenced by linguistic dominance. He pointed out that in India, languages listed in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution enjoy formal status, while others struggle for institutional backing. He addressed the ongoing debate about whether Kok Borok, historically lacking a uniform script, qualifies as a formal language.

However, he argued that a language’s essence lies in its spoken form, not just its written script. He drew parallels between the dominance of Hindi, Sanskrit, and English in India and global linguistic hegemony, where smaller languages face extinction risks. He stressed that language is dynamic, evolving with cultural and technological changes.

A key aspect of Professor Kalai’s research is the transformative impact of digital technology on Kok Borok’s representation. He explained that while print media often marginalizes languages without formal scripts, digital platforms have revitalized indigenous voices. He highlighted the use of cinema, documentaries, music videos, and social media clips as powerful tools for self-representation. He noted the shift from external representation by mainstream media, often distorting indigenous narratives, to self-representation through filmmaking and digital content creation by the Kok Borok-speaking communities.

He further noted that Kok Borok, previously known as the Hill Tiperah language, has been documented in British archives since the 18th and 19th centuries. He explained that the term “Kok Borok” means “language of the people.” Despite its historical depth, the language faced exclusion from official policies and mainstream media for many years, but digital technology has played a crucial role in its resurgence.

Regarding the future of regional cinema, Professor Kalai acknowledged the challenges faced by regional filmmakers, similar to those in Bollywood and Hollywood. He expressed his belief that storytelling transcends geographical boundaries, citing the global acclaim of filmmakers like Satyajit Ray as evidence that locally rooted stories can achieve international recognition. He advised aspiring filmmakers and content creators to curate content critically and maturely, emphasizing the unprecedented opportunity provided by the digital space for indigenous communities to share their stories.

In his concluding remarks, Professor Kalai stated, “Who am I to restrict the language? It will flow even after 1,000 years,” expressing his confidence in the enduring nature of Kok Borok.